Fresh Produce as a Status Symbol

Fresh produce as a status symbol, Grocery prices, The Umami Theory of Value, The effects of Trump’s tariffs, Meghan's new show and more!

Hey all!

This week we’re talking about the marketing of food, specifically fresh produce with luxury brands, the cost of groceries across America, Trump’s tariffs, and Meghan Markle’s new show.

A bit of a heavier newsletter this week, so with that in mind, I thought I would begin the newsletter on a lighter note with a shoutout to Parker Posey. She has come back on everyone’s radar with the latest White Lotus Season but for me, she will always be Victoria Ratliff in Best In Show (not to mention Party Girl). She deserves all the praise she’s getting. For now, I’ll keep practicing my South Carolinian accent “Tsunami… Buddhism…Piper noooo".

This week’s newsletter:

Fresh produce as a status symbol

The Umami Theory of Value

With Love, Meghan

A brief outline of the effects of Trump’s tariffs on the food and wine industry

The messed up grocery prices across America

Fresh produce as a status symbol:

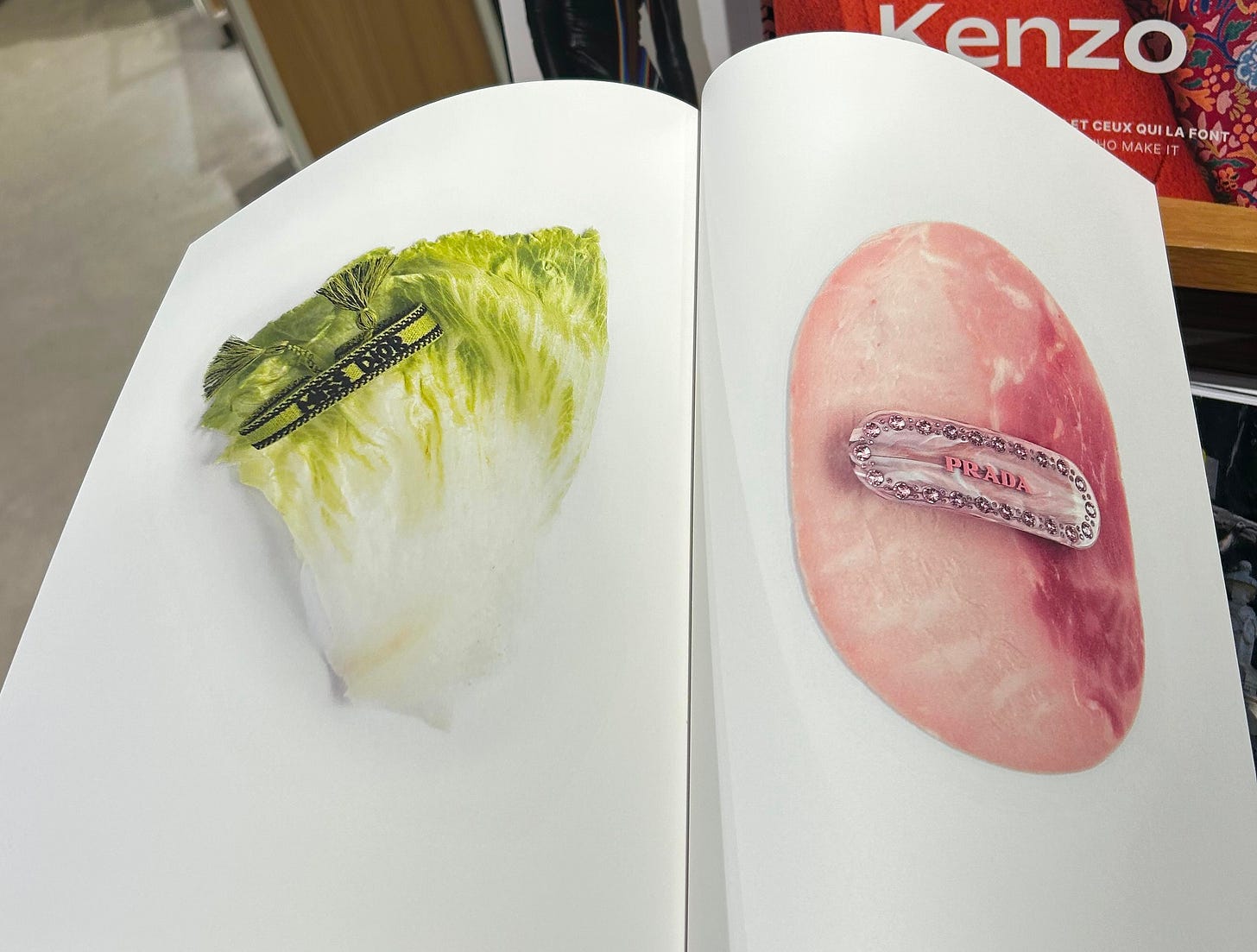

Food has always been a symbol of wealth, Marie Antoinette’s “Let Them Eat Cake” probably comes to mind. Each decade has had its own food politics of exclusivity and wealth signaling. Perhaps then, it is not surprising that as the price of groceries rises, basic fresh produce continues to rise as a luxury status symbol. Fresh produce as a status symbol feels like it has an extra punch and tone-deafness considering food prices have risen 28 percent (as of 2024), according to the Consumer Price Index, and many Americans are struggling to put the exact fresh produce marketed on their tables.

“The UK recently experienced one of its largest “cheese heists,” with 22 tons of cheddar cheese — worth nearly $600,000 — stolen.” Similar ‘heists’ and everyday theft of basic groceries like fruit, butter, and oil are occurring all over the world.

For the TikTok inclined, @kfesteryga on TikTok has a series on food as a status symbol. She has been tracking the growing trend of groceries and food as a status symbol in fashion and marketing for the past few years.

She does a great job at exploring the ways in which the cost of living crisis and class politics have infiltrated and fuelled many of the trends in fashion, art, and lifestyle over the past few years. In one of her videos she captions “Art has always used precious commodities to codify what’s culturally important but who ever expected its medium to be food”?

Hailey Beiber’s latest photoshoot seems to represent the latest evolution in this phenomenon. The food showcased in question, no longer even has to be ‘luxury’ or extravagant but just basic groceries…

As Elizabeth Goodspeed writes in It’s Nice That: “In Dutch paintings and Penn’s still lifes, food is the protagonist. But in contemporary advertising for beauty and fashion, food is the supporting actor. The inclusion of an ice cream cone in a photo of a purse is illustrative, not instructive — no one wants you to eat the purse or wear the cone. The food creates context and narrative for the product being sold.”

The Umami Theory of Value:

The other interesting angle to look at is the food/luxury/advertisement nexus from the unami theory of value. Published 5 years ago at the beginning of the pandemic, Nemesis (an alternative consulting agency that works with clients in luxury, deep tech, and culture) recently reposted their article titled ‘The Umami Theory of Value: Autopsy of the Experience Economy’.

On a business trip Emily, one half of the consulting duo Nemesis was taken to a new popular restaurant filled with young people and was struck by the realization that “People no longer want sex. They want umami.”

The article moved on from this statement to dive deeper into the theory of unami and experience economy. But when I look back at the trends in food, wine, and cocktails over the past few years and how we market them, this point sticks out. The industry has been trying to evolve for the upcoming generations that drink less, date less, and are coming of age in a cost-of-living crisis.

Umami as a flavor that describes the delicious savoury thick flavor was first scientifically identified by Kikunae Ikeda at Tokyo Imperial University in 1908. It often explains classic food pairings.

So, what is the umami cultural thesis?

“What do we mean by umami? Not only the meatiness of the French dip sandwich at that restaurant, but also the light as it refracted through the amber liquid of the cocktails, the reflection off the back bar, the quivering of the cake, and, most significantly, the way those elements read in a photo.”

“We believe that umami has been both literal and figuratively the key commodity of the experience economy”

Nemesis extend the definition of umami to popular culture, explaining the deconstructed, contradicting, ironic, and referential nature of an economy and society increasingly driven by ‘vibes’.

As Paris Starn, food artist and designer, recently said in an interview for Semaine “Food is an experience, regardless whether that’s simply visual or gustatory”.

“The Umami Theory of Value centers on losing your sense of what’s trivial and what’s valuable.”

“Cultural umami is the vague sense that yes, for some reason, it is. ““This shouldn’t be good but it is” “This doesn’t seem like what it’s supposed to be””

I think the umami culture theory is captured literally in the advertising we are seeing, the attempt to combine the perceived ‘trivial’ and valuable. Except, they’re out of touch with what’s trivial to most of the country at the moment.

A brief outline of the effects of Trump’s tariffs’ on the food and wine industry:

On the 6th of March Trump “doubled the 10 percent tariff on Chinese goods to 20 percent and put 25 percent tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada. The three countries are America’s biggest trading partners.” The Food Policy Tracker reports that economists say “say tariffs will likely lead to higher food prices, while farmers are worried about fertilizer imports and their export markets.” The following day, due to pushback from agricultural groups and lawmakers, Trump temporarily “exempted products covered under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) from tariffs until April 2.”

The key impacts outlined in an article published by the Food Policy Tracker were fertilizer imports, 85% of mineral fetilizers used by American farmers come from Canada. Likewise, “China is the biggest export market for American farmers. In response to Trump’s tariffs, the country announced it will reciprocate with 15 percent tariffs on American food and agricultural products including soybeans, meat, and chicken.”

Perhaps most relevant for you guys is that “beyond farmers, economists say everyday Americans should expect higher food prices. That’s because the U.S. imports about $200 billion in food, beverages, and animal feed from the three countries, especially fruits and vegetables from Mexico and animal feed, grains, and meat from Canada. In the past, importers have passed the cost of tariffs on to consumers.”

And from the Financial Times: “The US economy isn’t in great shape to take a bunch of self-inflicted blows. Expectations of the effect of tariffs — and of policy uncertainty more generally — are already evident. Business and consumer confidence is weakening, consumers’ inflation expectations are rising, the stock market has had a bad time and there have been some well-publicised price shocks like eggs, whether tariff-related or not.”

Trump has also threatened to impose a 200% alcohol tariff on the EU. In response to their plans to impose duties on US products, including a 50% levy on whiskey (they have since delayed this) which was in response to Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs. A giant tit-for-tat set of tariff-ing which isn’t good for anyone.

He also gave this insane explanation “I’ve always liked American wines better than French wines. Even though I don’t drink wine… I just like the way they look.”

The messed up pricing of groceries across America:

To go back to groceries, and why the current marketing feels extra icky at the moment, I thought I’d talk about grocery prices and the cost of living. Kate and I have been moving around the country for the past few years which has given us a real insight into different living standards and prices in different states. What I have noticed is how much more expensive groceries are in rural areas.

There are some obvious reasons, transportation, trade routes, demand, monopolies etc. But the disparity and our disconnect from where our food actually comes from really frustrated me.

Rural areas comprise less than two-thirds of all U.S. counties, but 9 out of 10 counties with the highest food insecurity rates are rural. A huge part of this, is the cost of fresh produce in rural areas. Everyone is feeling the pinch of the cost of living crisis, but people in rural areas are experiencing it even harder than most.

“In the United States, food moves from field to fork through many channels, including: producers, first-line handlers/manufacturers, wholesale/logistics, retail food/food service sector, and the consumer. Food is occasionally sold directly from producers to consumers, but a majority of food travels through the other channels.”

This means that food grown in America begins at farms in rural areas and has a huge journey before actually getting to the plates of those farmers and communities. Raising the costs for the very communities growing some of produce, and people who are already doing it tough.

We have a deep disconnect between where our food comes from and where it ends up. We have become increasingly alienated from the production of our food. Further, because every stage of production has been broken down and separated for efficiency and cost, and so much of this has been outsourced, it is almost impossible for us to be self-reliant. Due to the supermarket monopolies and lack of options in rural areas, people don’t have a cheaper choice.

“From farm to fork, America’s food system has been rooted in the exploitation of women, Native Americans and people of color. This is at the heart of capitalist food politics – big corporations taking as much as they can and paying as little as possible for it,” said Raj Patel, academic and author of Stuffed and Starved: Markets, Power and the Hidden Battle for the World's Food System.

This is both a race and class issue too, with more lower-income earners and people of color living in rural areas. The higher costs of groceries contributes to already growing disparities in health, wealth, and food insecurity.

It’s a little older (2021) but The Guardian has an interactive article on the true extent of America’s food monopolies and who pays the price. Only a handful of powerful companies control the majority market share of almost 80% of dozens of grocery items bought regularly by ordinary Americans.

People who harvest, pack and sell us our food have the least power, in fact only 15 cents of every dollar we spend in the supermarket goes to farmers. The rest goes to processing and marketing our food.

“Less competition among agribusinesses means higher prices and fewer choices for consumers”. Corporate consolidation can drive up food prices and reduce access to food. Over the past 40 years, farmers are paid less and consumers are being charged more.

“While the United States has many programs at the state and federal levels to alleviate food insecurity… these policies are typically a “one-size fits all” approach, meaning that counties are treated equally, regardless of their rural/urban classification or trade flows.”

With Love, Meghan:

Finally, on a very different note (or perhaps not so different) Meghan Sussex (formerly Markle) has a new Netflix series out and people have a lot of thoughts but everyone can agree it’s pretty bad but fairly innocuous. In a Gwyneth Paltrow-esq turn, Meghan Sussex has pivoted to domestic guru. Cooking, table-scaping, party bag planning, honey collecting, and awkward small talk with guests.

Marina Hyde had an interesting take on the Guardian which I think ties into our discussions of wealth, food, and politics:

“Maybe, Meghan has made a landmark TV series after all. Immerse yourself in it for an episode or eight, and you instinctively feel that both the show and the duchess embody the age that has become suddenly bygone. And that is the exact feeling that countless people have been experiencing since this year turned – that an era is dying. Or rather, that it has already died, and suddenly. There were many others, but Meghan was as good an avatar for it as any – torn between wildly ineffective social justice activism, and the narcotising retreat of the peonied table.”

That’s all for this week! Good job if you made it all the way through, I promise things will be a little lighter on next week.

Carlie xx